Birth and maternity culture in England 2024

Our expert solicitors at Barcan+Kirby analysed the results of the 2023 Maternity Survey, released on 9th February 2024. The data revealed some significant and often shocking findings regarding birth and maternity culture in England.

It appears that a significant number of people are receiving inadequate birth and maternity care and that, in certain areas, these failings have become more prevalent over the last few years.

The 2023 CQC Maternity Survey involved over 100 NHS trusts in England that provide maternity services, and consists of responses from 25,515 women. Women were eligible for the survey if they had a live birth under the care of a participating trust between 1st and 28th February 2023, and January if a trust did not have a minimum of 300 eligible births in February.

With 35% of people surveyed considering making a complaint about the care they received at any point during their maternity care journey, we look at the data in more detail…

Key statistics from the 2023 Maternity Survey

- Almost 1 in 5 people felt they didn’t have the right information at all to make an informed choice about where to have their baby.

- Almost 1 in 3 (31%) people weren’t given appropriate information and advice on the risks associated with induced labour, whilst 14% were not involved in the decision to be induced.

- Around 1 in 4 said they were not always involved in decisions about their care during labour and birth, and 27% said the same during post-natal care.

- During antenatal check-ups, 1 in 5 said they didn’t always feel they were given enough time to ask questions or discuss their pregnancy, and 17% said they didn’t always feel listened to by their midwife.

- Throughout care, around 1 in 4 said the midwife or midwifery team did not always listen to them.

- Around 1 in 5 (18%) expectant mothers were not offered a choice about where to have their baby.

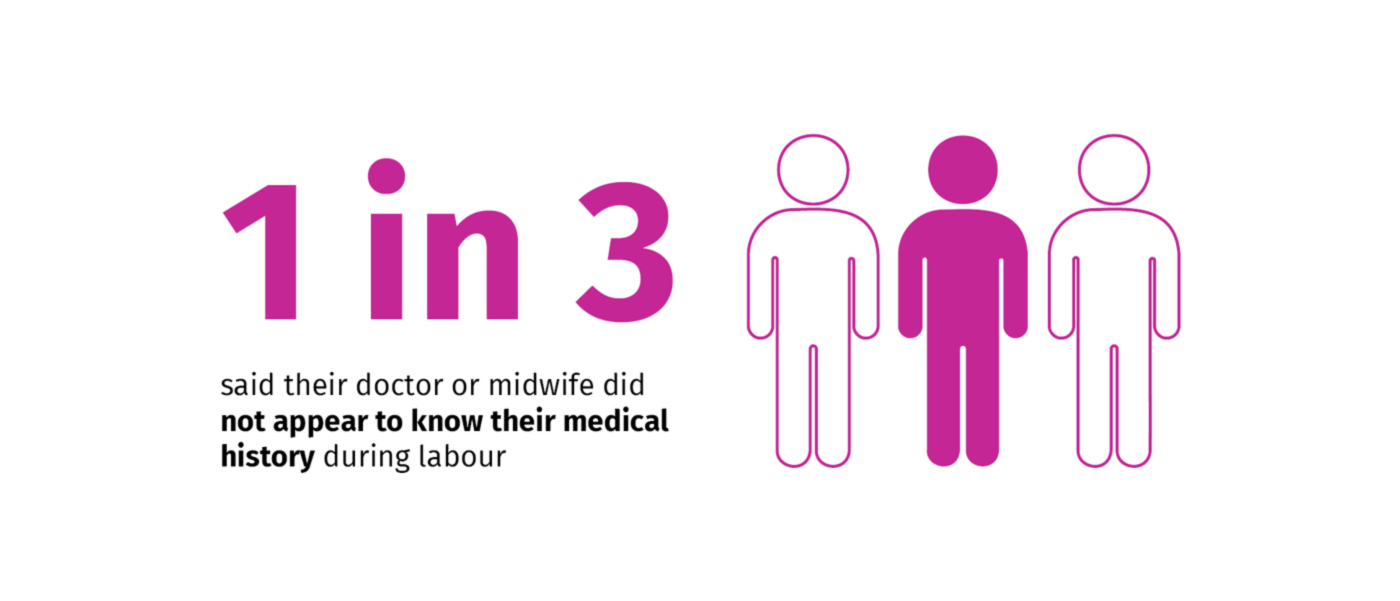

- When attending antenatal check-ups, 76% of people did not see the same midwife every time, with just under 1 in 2 (46%) saying the doctor/midwife did not always appear to know their medical history during their antenatal check-ups, and over 1 in 3 during labour.

- 59% said the midwives who cared for them postnatally were not involved in their antenatal care or labour.

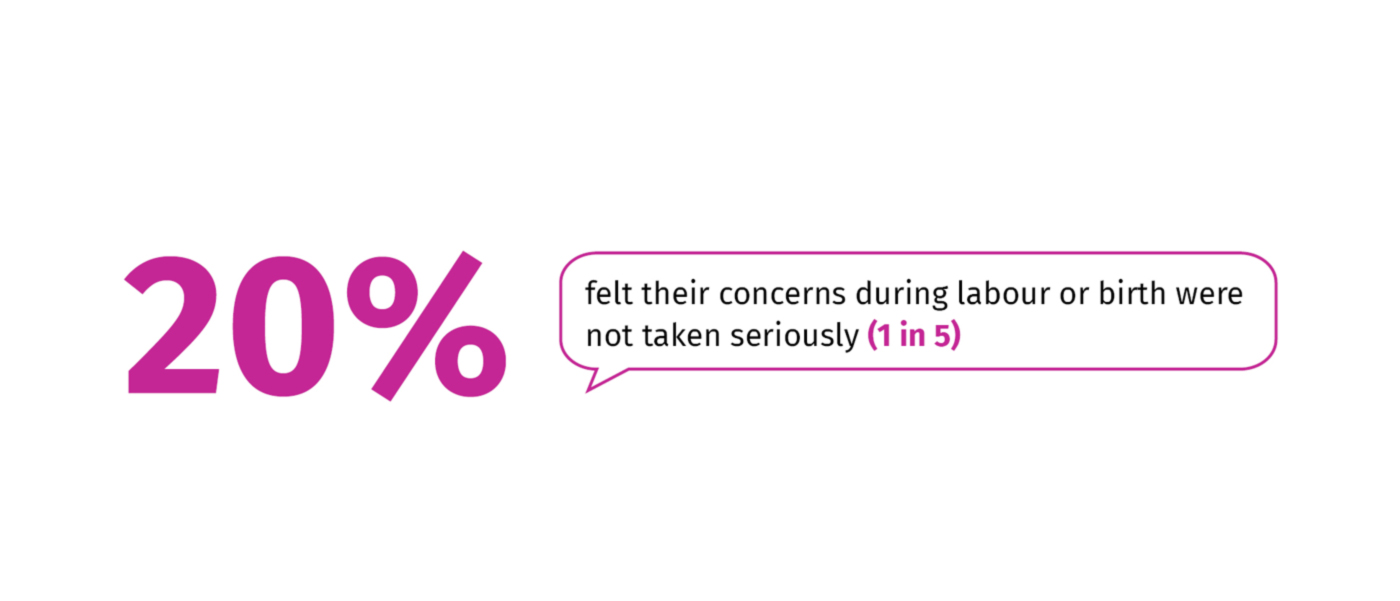

- When raising a concern during labour or birth, 1 in 5 people felt that it was not taken seriously.

- Reflecting on antenatal care, 13% felt they weren’t always treated with respect, and 12% felt they weren’t always spoken to in a way they could understand.

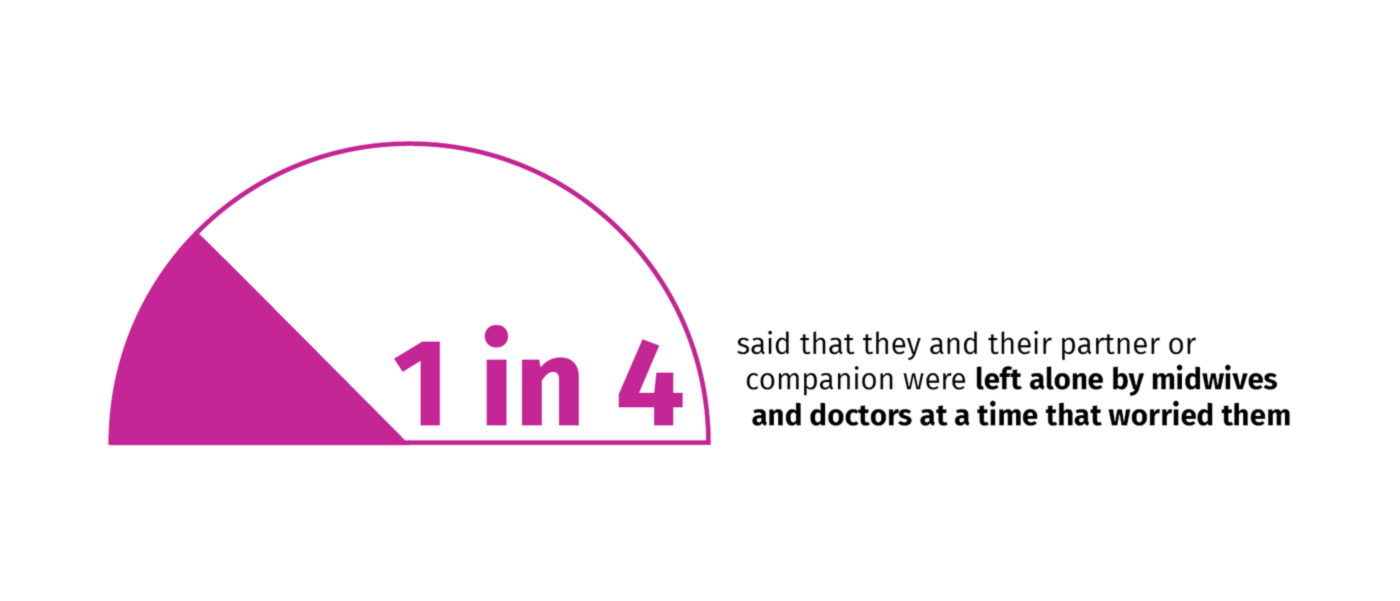

- 1 in 4 said that they and their partner or companion were left alone by midwives and doctors at a time that worried them.

- When trying to get help from a member of staff, over 45% agreed they weren’t always able to get help.

Birth and maternity culture data and analysis 2023

Birth and maternity continuity of care

Participants of the survey were asked who was the first health professional that they spoke to when they believed they were pregnant. The data revealed that:

- The number of people who saw a doctor initially when they thought they were pregnant has decreased year on year, at 63% in 2013 down to 28% in 2023.

- The number of people who saw a midwife initially has increased year on year from 32% in 2013 to 66% in 2022.

- 5 to 7% of people saw a different health professional

This data indicates a growing preference to see a midwife as opposed to a doctor when someone first discovers that they may be pregnant.

Midwives are typically viewed as offering a continuity of care during pregnancy, labour, and birth, as well as postpartum care. Many who are pregnant may prefer the idea of a consistent and personalised experience, instead of receiving care from various doctors at different stages, which may explain these trends.

That said, the data reveals that, when attending antenatal check-ups, 76% of people did not see the same midwife every time, and 46% of people said the doctor/midwife did not always appear to know their medical history at this time.

Similarly, during labour/birth, 38% of people said the doctor/midwife did not always appear to know their medical history at this stage. What’s more, 82% of people said that the midwives who cared for them during antenatal care were not involved in their postnatal care.

Research from Birth Rights indicates that continuity of carers “has been shown to lead to fewer preterm births and fewer people losing their baby in pregnancy or the first month following birth.”

The fact that so many are not accessing this type of care means that they may experience health complications and even fatalities that could have been prevented. It suggests what we may already know; the NHS are understaffed and overworked, and individuals are thus unable to provide regular care for the same people.

These failings are echoed in the way that pregnant women feel about their experiences. For instance, 23% of people did not ‘definitely’ have confidence in the staff who cared for them during their labour and birth, and 28% of people did not ‘definitely’ have confidence and trust in the staff who provided their antenatal care.

Information during and regarding pregnancy, birth and postpartum

The survey data revealed some concerning revelations about the information that people received during pregnancy.

When participants were asked whether they received enough relevant information about where to have their baby, and information about feeding their babies, the data revealed:

- Only 54% felt they were ‘definitely’ given enough information about where to have their baby.

- Almost 1 in 5 felt they didn’t have the right information to make an informed choice about where to have their baby.

- Only 55% of people felt they ‘definitely’ had the relevant information about feeding their babies, with 30% saying they sometimes did, and 14% saying they didn’t at all.

As we can see, a significant amount of people did not feel properly, or at all, informed at various stages.

The survey revealed a similar lack of education about induction. When asked whether they received enough information on induction prior to being induced, including information and advice on the risks associated with induced labour, the collective answers showed:

- 14% felt they weren’t involved in the decision to be induced.

- Almost 1 in 5 (19%) of people weren’t given appropriate information and advice on the benefits associated with an induced labour.

- Almost 1 in 3 (31%) people weren’t given appropriate information and advice on the risks associated with an induced labour.

The data is deeply concerning, showing a significant lack of education for expectant mothers.

Induced labour can pose a number of potential risks and complications. Lack of education in this area amounts to risking the health and lives of mothers and their children.

These stats indicate a prevalence of substandard pregnancy health care, further supported by a recent BBC analysis of Care of Quality Commission records which showed that a shocking two-thirds of maternity units are not safe enough.

Birth and maternity choices and informed consent

The prevalence of education and available information for expectant mothers gives rise to questions surrounding informed consent.

Survey answers revealed that not all people were given key choices about their antenatal care and, as such, may not have given informed consent for their induction, amongst other revelations:

- 18% were not offered a choice about where to have their baby.

- 14% said they were not involved in the decision to be induced.

- 1 in 5 people felt they weren’t always involved in decisions about their antenatal care.

- Almost 1 in 4 said they were not always involved in decisions regarding their care during labour and birth.

- Reflecting on postnatal care, 27% said they were not always involved in decisions.

Having a home birth as opposed to a hospital birth comes with potential health risks to both mother and baby, which is why it is vital that people are given a choice, as well as educated on the potential risks.

Induced labour also poses health risks, and so being induced without consent may amount to negligence claims, particularly where the induction has resulted in complications.

When asked if people felt that their midwife listened to them during their antenatal check-ups, the data showed that 17% said they didn’t always feel listened to by their midwife. Additionally, 1 in 20 people felt their decision on how to feed their baby wasn’t respected.

As we can see from these statistics, many people did not feel well-informed, listened to, or respected regarding their pre- and post-natal care, and a significant number may not have consented to how their labour and birth experience was handled by health care providers.

These findings indicate that the systems in which women access healthcare and support when they are pregnant are in need of reform. It also suggests our healthcare system is putting itself at unnecessary risk of being sued for negligence.

The previously mentioned BBC analysis of the CQC further revealed that ‘the proportion of maternity units with the poorest safety ranking of “inadequate” – meaning that there is a high risk of avoidable harm to mother or baby – has more than doubled from 7% to 15% since September 2022.’

In cases where women have experienced birth injuries due to negligence, or injuries due to health treatment that they did not consent to, these women will have grounds for a maternity compensation claim.

Post-partum mental and physical health information

Mental health during and after pregnancy

When asked if they were given enough support for their mental health during pregnancy, over 1 in 10 (12%) said no. Similarly, when asked whether they were given information regarding any changes to their mental health which might be experienced after having their baby, only 60% said yes they definitely received this, whilst the rest were left unsure.

Additionally, 17% of people said that they were not told who they could contact if they needed advice regarding mental health changes experienced.

Stats like these are incredibly troubling, exposing a significant failing of healthcare providers regarding the mental health of new mothers.

NHS data indicates that a quarter of people experience mental health issues during pregnancy or postpartum. Issues that pregnant or new mothers may experience include depression, anxiety, and post-partum psychosis. NHS research further indicates that suicide is a leading cause of death both in pregnancy and in the six-week postpartum period, which has seen an increase over the last few years.

According to the Birth Trauma Association, there are 30,000 new cases of postnatal PTSD in the UK every year, also referred to as birth trauma, a condition that can be confused with postnatal depression. Additionally, 30% experience a few symptoms of postnatal PTSD, without fully developing the condition.

With this data in mind, it is easy to see why adequate mental health support for pregnant women is an absolute necessity, both during pregnancy and after birth. The prevalent and continued lack of support puts so many women and their families at risk.

Physical health during and after pregnancy

Regarding information on physical recovery after birth, the data revealed:

- Over 1 in 2 were left uncertain or completely in the dark.

- 15% weren’t given information about physical recovery from birth in 2023, which has increased from 10% in 2019.

- 38% of people said they didn’t think their healthcare professionals did everything they could to help manage their pain during labour and birth, and 34% said the same after birth.

Receiving information about physical recovery after birth is crucially important, and the fact that less people believe that they are receiving this information in 2023 compared to 2019 is worrying.

It indicates that subpar healthcare during pregnancy is all too common considering the potential injuries that can occur as a result of giving birth, including pain or discomfort due to a healing episiotomy, perineal tears, or pelvic floor damage. These trends in part indicate that healthcare institutions are increasingly understaffed and underfunded, and that this affects the quality of care that people are receiving.

Humanity and mental health care, pre and post-natal

Specific questions were designed to assess humanity in pregnancy health care, as well as mental health care, both pre and post-natal. The data revealed that:

- 1 in 5 felt that if they raised a concern during labour and birth, it was not taken seriously.

- When receiving antenatal care, 12% felt they weren’t always spoken to in a way they could understand.

- 13% felt they weren’t always treated with respect and dignity when receiving antenatal care.

- Over 1 in 10 said they were sometimes treated with respect and dignity during labour and birth, and 3% said they were not at all.

- When reflecting on the care received in hospital after birth, over 1 in 5 people said they were only sometimes treated with kindness and understanding, and 6% said they were not at all.

- During the postnatal check-up, only 39% of people felt that the GP spent enough time talking to them about their own physical health, and only 41% of people felt that the GP spent enough time talking to them about their own mental health.

As we can see, many people did not receive an adequate standard of care where they were treated with respect, and where their concerns were listened to.

This is concerning for a number of reasons. It is crucial to involve people in decisions regarding their bodies and birth experiences. Failing to hear a person’s concerns threatens autonomy in labour and birth, and undermines the quality of healthcare the people are receiving.

Survey participants were also asked about their stay in hospital whilst pregnant and giving birth. The data revealed that 37% of people in 2023 said their partner, or someone involved in their care, was restricted to visiting hours. Although this figure has massively improved since 2021 (63%) and 2022 (56%), it still indicates that over 1 in 3 are not receiving much-needed regular support from their partners or loved ones during labour/birth.

Naturally, those who are pregnant, giving birth, and receiving postnatal care require support from their loved ones. We can fairly assume that these stats indicate a less comfortable experience for pregnant people likely to have impacted their mental health.

As discussed earlier, mental health support is crucial for those who are pregnant and in their post-partum phases, and many are at risk of developing serious mental health conditions. This absence of consistent support, kindness and respect only further escalates the issue.

Ease of contact in maternity care

Participants of the survey were also asked questions about ease of contact during maternity care. The data showed that:

- 73% of people in 2013 felt they were always given the help needed after contacting the midwife, which has fallen to 72% in 2023.

- Over 1 in 5 said only sometimes did they feel they were given the help needed after contacting the midwife.

- 5% of people said they didn’t get the help they needed, or that they couldn’t get hold of a midwife at all.

- 1 in 4 said they were left alone by a doctor or midwife at a time that worried them.

When asked whether they were able to get help from a member of staff during labour and birth, almost 1 in 5 agreed they weren’t always able to. During post-natal care, almost 1 in 2 (44%) said the same.

It appears that ease of contact is another issue that people are experiencing during the pregnancy and postpartum phases, and that many have been left unable to access key help and support when they needed it.

How can Barcan+Kirby help

The data depicted tells a sad tale of the state of our NHS maternity services. It’s clear that a huge overhaul is needed to support workers in maternity and to ensure pregnant people are treated with the dignity and respect they deserve to give birth how they want to.

If you’ve experienced a birth injury as a result of medical negligence, our expert solicitors at Barcan+Kirby can assist you.

Our highly accredited and experienced solicitors have worked on a wide range of birth injury cases, with an excellent track record. For more information, call us on 0117 325 2929 or complete our online enquiry form.